With the major impact of climate change, we are facing increasingly challenging and extreme weather. During the New Year period of 2026, the named winter event Anna hit Sweden with strong winds and heavy snowfall. This led to power outages, disrupted railway traffic, dangerous road conditions, etc. In Gävleborg in particular, it caused severe disruption—including widespread outages and major travel and transport paralysis—prompting authorities to issue a red warning. Can we know better where, when, and how such events will come for a better preparation for the future? We are expecting an answer from AI for science. And Microsoft Research AI for Science provides a foundation model AURORA for this.

In this post, let’s have a look at AURORA together.

Problem

According to the paper, traditional earth system forecasting models are computationally demanding, built with high engineering complexity, and use approximations with sub-grid scale processes. In contrast, AI-based methods outperform traditional methods, especially on the global medium-range weather forecasting at 0.25 resolution. Compared with other AI-based forecasting models, AURORA with a larger number of parameters is trained on a diverse range of datasets including forecasts, analysis data, reanalysis data, and climate simulations. It achieves state-of-the-art performance on several forecasting tasks.

Note: On the one hand, the limitations are actually general problems of all systems, which don’t seem specific to the non-AI forecasting methods. On the other hand, the advantages of using current deep learning methods can be from the ability of generalization like transfer learning, zero-shot and few-shot learning. Moreover, for using foundation models, the advantage can be training a system for all tasks at the same time with all possible datasets instead of using one dataset for one task. We expect that in this way generalization can be achieved at scale. This requires a proper collection of datasets and a capable model. Moreover, AURORA can be fine-tuned for different downstream tasks with a good performance as well.

Model

Each module deserves a separate blog, so only high-level descriptions are introduced here.

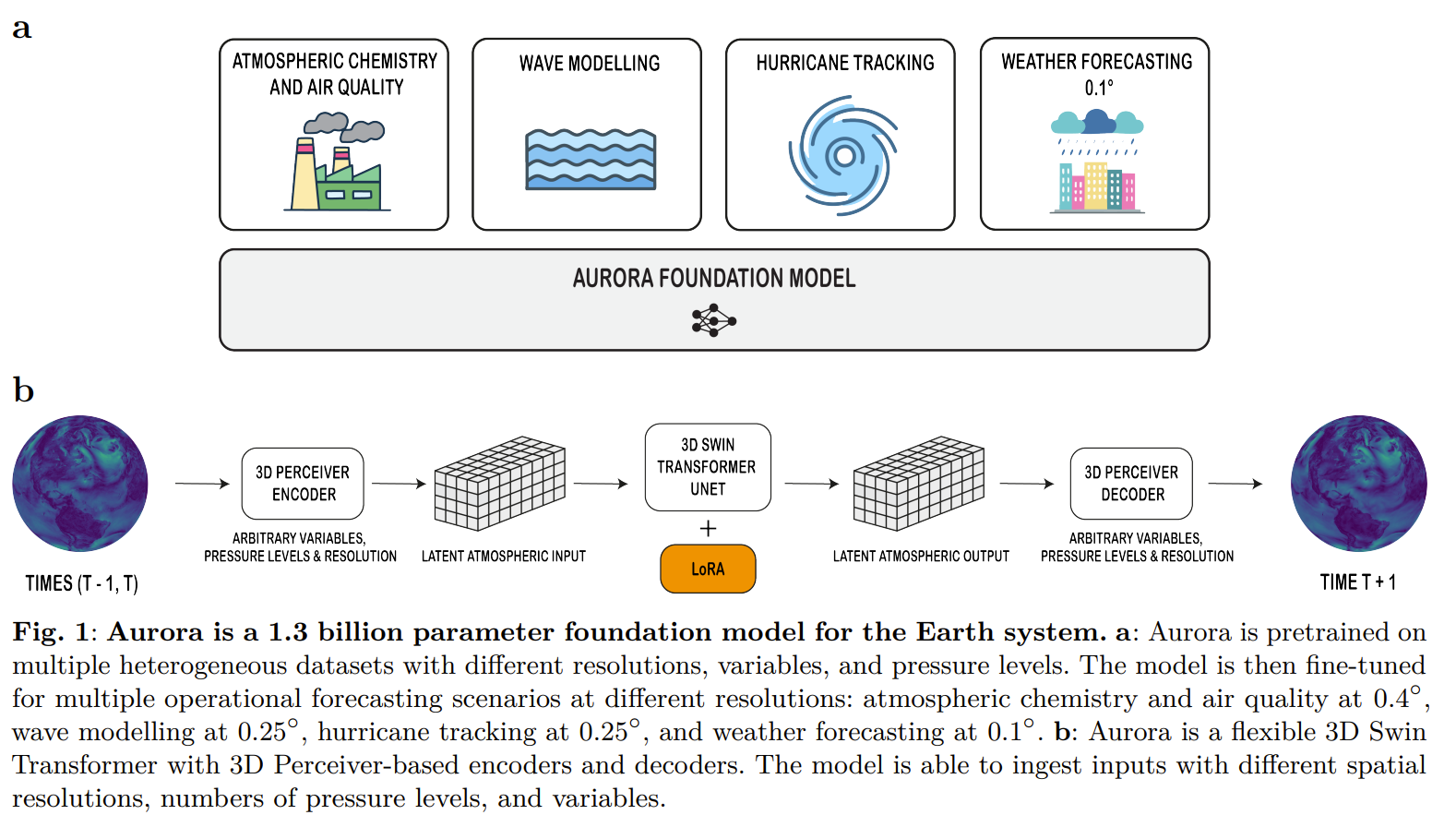

Figure: Aurora workflow and architecture (pretraining → fine-tuning & inference). Source: Microsoft Research blog post.

Figure: Aurora workflow and architecture (pretraining → fine-tuning & inference). Source: Microsoft Research blog post.

Perceiver-based encoder-decoder (Jaegle et al., 2022). A primary reason for using Perceiver is to deal with input data with different formats, modalities, and dimensionality. And Perceiver IO (Jaegle et al., 2022) was proposed for dealing with this problem. Moreover, reducing the dimensionality makes the processor lightweight. One more potential benefit is that the processor may have difficulties in handling high-dimensional data, e.g., Transformer-based diffusion models often rely on latent diffusion model solutions.

Normally, the latent representation with encoders is expected to be able to learn abstract concepts by compression and reconstruction. Representation with Transformers is interesting, that generalize the [CLS] token trick. A concern here is that whether this way of learning representation can lead to useful compact representation capturing essential dynamics for forecasting. Furthermore, whether the representation which is helpful for forecasting is helpful for other tasks.

Query-based decoding was proposed in (Jaegle et al., 2022) which is used for multi-modal foundation models like Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022) and BLIP-2 (Li et al., 2023). The latent representation works as an abstraction together with an output query to generate the target in the expected domains.

A processor: Modified Swin Transformer U-Net (Liu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). Originally, Swin Transformer was proposed for dealing with the computational issues of Transformers when applied to tasks requiring dense prediction at the pixel level like segmentation tasks. It achieves linear computational complexity by restricting the global attention over all patches of an image to be within windows of an image. Moreover, it uses linear layers for merging patches and changing the dimensionalities.

For dense prediction, it is not necessary to be handled with Swin Transformer, like SAM 1-3 (Kirillov et al., 2023; Ravi et al., 2024; Carion et al., 2025). So it remains interesting to see how a plain ViT (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021) would perform.

Training recipes.

Some thoughts about the training objective: It is reasonable that for computational considerations, one-step prediction with one past step is used; however, it remains interesting to see the benefits of using more information from temporal perspective and, a probabilistic perspective, like latent diffusion models.

| Pretraining aspect | |

|---|---|

| Objective | Minimize next time-step (6-hour lead time) MAE |

| Steps | 150k steps |

| Hardware | 32× NVIDIA A100 GPUs |

| Wall-clock time | ~2.5 weeks |

| Batch size | 1 per GPU (global batch size 32) |

| Data used (high level) | Mixture of forecasts, analysis, reanalysis, and climate simulations (details in Supplementary C.2) |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate schedule | Linear warm-up from 0 for 1k steps, then (half) cosine decay; base LR 5e−4, decays to 1/10 by end |

| Weight decay | 5e−6 |

| Regularization | Drop path (stochastic depth) with probability 0.2 |

| Precision | bf16 mixed precision |

| Memory/parallel efficiency | Activation checkpointing (backbone layers) + shard gradients across GPUs |

Discussion

- What is a foundation model?

- What are we expecting from foundation models?

- What are beneficial discussions for the AI for science community?

- What is beneficial analysis in experiments?

- Should we worry about data for AI for science compared with web-image-text for other foundation models?

- A concern on finetuning regime.

Further Reading

- Swin Transformer (Liu et al., 2021)

- Perceiver IO (Jaegle et al., 2022)

- ClimaX (Nguyen et al., 2023)

- GraphCast (Lam et al., 2023)

- NeuralGCM (Yuval et al., 2025)

References

- Dosovitskiy, A., et al. (2021). An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. ICLR.

- Liu, Z., et al. (2021). Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. ICCV.

- Alayrac, J. B., et al. (2022). Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning. NeurIPS.

- Jaegle, A., et al. (2022). Perceiver IO: A General Architecture for Structured Inputs & Outputs. ICLR.

- Liu, Z., et al. (2022). Video Swin Transformer. CVPR.

- Kirillov, A., et al. (2023). Segment Anything. ICCV.

- Lam, R., et al. (2023). Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science.

- Li, J., et al. (2023). BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. ICML.

- Nguyen, T., et al. (2023). ClimaX: A foundation model for weather and climate. ICML.

- Ravi, N., et al. (2024). SAM 2: Segment Anything in Images and Videos. arXiv.

- Bodnár, C., et al. (2025). A Foundation Model for the Earth System. Nature.

- Carion, N., et al. (2025). SAM 3: Segment Anything with Concepts. arXiv.

- Yuval, J., et al. (2025). Neural general circulation models for modeling precipitation. Science Advances.