Talking about continual learning, very likely we may talk about different things, like AGI. It can be

- the post-training of LLM;

- self-evolve agents;

- experience replay in DQN (Mnih et al., 2013);

- sequential learning of MNIST digits;

- optimal order of learning tasks, …

For a better conversation, this post aims at bringing back the context of continual learning in deep learning, positioning it together with other learning regimes, show the definition, evaluation, and solutions without technical details. Moreover, discuss the connection and inspiration for LLMs and foundation models. This post is inspired by (Mundt et al., 2023).

Context

We are in the era of foundation models. Foundation models are often large and specified at the beginning. A popular way of training such models is to train from scratch between versions, like DINO (Caron et al., 2021) and CLIP (Radford et al., 2021). Does it have to be in this way? We may want to ask

- Can they evolve by themselves?

- Can they keep learning without from scratch?

- Can they use the learned knowledge to help learn from new data?

- Can they characterize new data as a ratio from known to unknown for update with a better plan like accumulating data for new knowledge until enough for training, update learned knowledge based on relevance and importance of new data?

Besides this technical aspect, we are looking for models that can keep learning with new data and expanding their capabilities of new tasks. However, the learning regime suffers from catastrophic forgetting, that deep learning models forget what learned before while learning from new data and new tasks. When we expect the model to accumulate knowledge and experiences, the forgetting is catastrophic. But catastrophic forgetting is the natural consequence of deep learning when the data distribution is shifted.

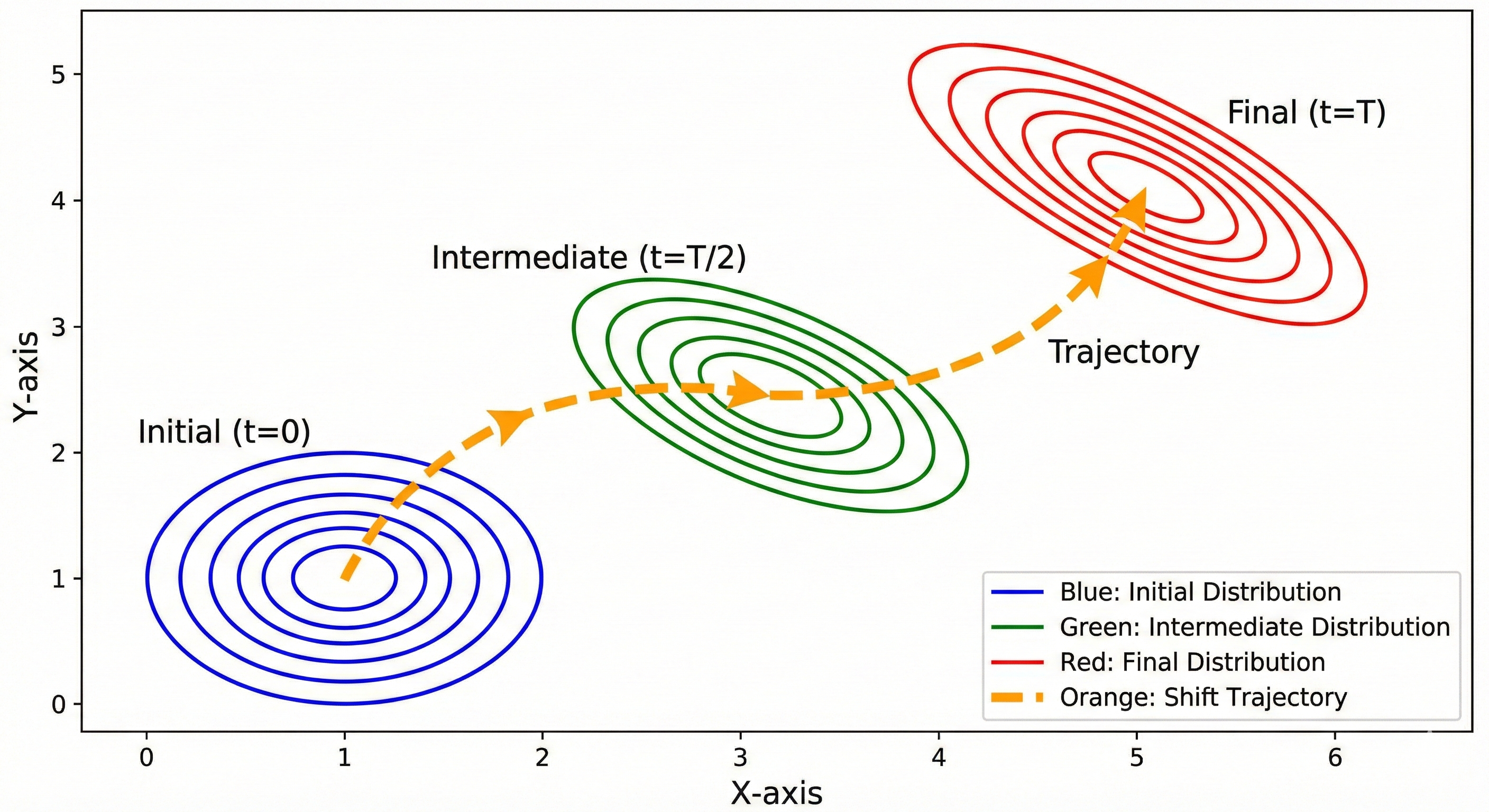

Figure 1: Catastrophic forgetting can be ideal. A data distribution is shifting from time 0 to time T. If T represents the current scenarios, an idea behavior should make models forget at time 0 and focus on time T.

Figure 1: Catastrophic forgetting can be ideal. A data distribution is shifting from time 0 to time T. If T represents the current scenarios, an idea behavior should make models forget at time 0 and focus on time T.

Moreover, new data and tasks can be conflicting with the old ones that makes the learning task challenging. In theory, we assume that test and training data distributions are the same. But in practice, they can always be different to some extent. Techniques that mitigate the discrepancy well for LLMs and foundation models are needed.

Furthermore, how could we understand the current useful techniques in LLMs and foundation models, Mixture of Experts (MoEs (Shazeer et al., 2017)), gating mechanisms (like in Qwen (Qiu et al., 2025)), RL-based post-training, EMA (like in DINO), synthetic data as training data (in TabPFN (Hollmann et al., 2023)).

An imperfect definition as a starting point

Suppose there are N tasks coming/streaming in sequence where $N \in \mathbb{Z}$, a model keeps learning for current task $i < N$ while not forgetting nor losing the capability for the past tasks for $t = 0,…,i-1$.

First of all, this is a result-driven definition requiring the model to perform well on all tasks given a sequence of tasks. Secondly, the definition is heuristic, like learning, forgetting, and losing without clear technical definitions. In summary, the characteristics are

- sequential/streaming data and tasks;

- the performanc should reasonably be good for all tasks, especially no forgetting for the past tasks.

Given limited resources and capabilities of models, this doesn’t make sense. For example, even for human, forgetting is common and sometimes better for learning. Especially, when new task conflicting with the past tasks and can generate new knowledge, maintaining the ability of past tasks doesn’t make sense. So sometimes there should be an interaction between past and current task. In that case, instead of avoiding forgetting, the model needs to update knowledge with new data / tasks and solve new tasks based on old tasks. Therefore, there is no one for all definition of continual learning. And we should modify the definition according to the requirements of applications.

Other learning regime.

- Transfer Learning / domain adaptation: often, there are two domains, source and target. And transfer learning aims at transferring the ability of deep learning models in th source domain to the target one. For example, finetuning for downstream tasks follows the regime.

- Multi-task Learning: Given all tasks at the same time, a model is required to perform well on all the tasks, e.g., LLMs are in this category.

- Online Learning: this is more like a optimization problem, when streaming data come sequentially, how to optimize the model on the fly.

- Few-shot Learning, in-context learning: few-shot, zero-shot learning requires a model to be able to work on minimal data and leverage the model (often a pre-trained model) to get the best performance on the task. This requires minimal or no updates of the model. For example, CLIP can work well with zero-shot transfer.

- Curriculum Learning: this emphasizes the learning/training process of deep learning models follows a well organized order of tasks, e.g., from simple to difficult, for a better training process.

- Active Learning: this try to query data or labels on the fly for a better training performance, that queries the least and achieves the best.

- Meta learning: emphasizes make a model learn how to learn which can quickly adapt to new tasks, e.g., MAML (Finn et al., 2017) provides a better initialization and helps update model parameters towards different tasks with fewer training iterations.

Evaluation

Datasets. Common benchmarks for continual learning of deep learning models are the modified MNIST, CIFAR-10, imageNet, that are used for constructing tasks and streaming new data over time. (Mundt et al., 2023) this paper also claims to use more realistic real open world datasets for measuring better the forgetting.

Metrics.

- Overall performance: measures how well a model perform over all tasks over time, like the average accuracy over tasks over time;

- Forgetting metric: measures how much a model forgets about a task when learning new tasks over time, like the performance drop of tasks over time;

- Other aspects: memory consumption, model size, robustness.

Categories of methods

There are mainly three categories for continual learning of deep learning methods before LLMs.

Architecture-based.

- static: this assumes fix model capacities like parameters. Updates of the parameters can be done by routing or gating, e.g. MoEs.

- dynamical: dynamical growth of models for more new tasks.

Experience replay-based. Two types of replay methods:

- Sample-based: choose the most representative data for maintaincing the perofrmance of old tasks.

- Generative model-based: use Generative models to generate data for replay while saving the storage of data.

Regularization-based methods try to limit or smartly decide (like updating according to the weight importances) changes of parameters or representation for new tasks and data.

Lessons from the past

(Mundt et al., 2023) summarizes the lessons.

Forgotten lesson 1: Machine learning models are by definition trained in a closed world, but real-world deployment is not similarly confined. Discriminative neural networks yield overconfident predictions on any sample. Forgotten lesson 2: Uncertainty is not predictive of the open set. Active learning resides in an open world and common heuristics based query mechanism are susceptible to meaningless or uninformative outliers. Forgotten lesson 3: Confidence or uncertainty calibration, as well as explicit optimization of negative examples can never be sufficient to recognize the limitless amount of unknown unknowns. Forgotten lesson 4: Data and task ordering are essential. Although this forms the quintessence of active learning it is yet untended to in continual learning.

Discussion

Boundary of tasks and hallucination (over-confidence). The boundary of tasks becomes less clear in NLP tasks. Because many of them can be formulated as sequence-to-sequence task and LLMs have be trained on such tasks during the pre-training phase with predicting next tokens. Thus, a unique and distinguishing point for LLMs is that a new task can very likely be formulated as the old tasks, and the tasks share certain common knowledge but not all. For example, the new task is coding and pre-training data are from web-text data. The pre-training data can cover the data of the new task but the distribution can be different from or insufficient for the test scenarios. (As same as deep learning models, LLMs are over confident in such scenarios.) In this case, active learning aims at querying the data for gaining the most information about the test data distribution and RL finetunes the model w.r.t the test task by interacting with the test environment.

Updating the known and learning unknown knowledge. Considering the knowledge as the representation and parameters of neural networks, updating the known knowledge and learning unknown knowledge mean updating parameters. When new data coming, different strategies can be applied if we can be characterized whether the data belong to known knowledge or unknown knowledge. But this is non-trivial, considering that anomaly detection and out-of-distribution detection are still active research areas. And data-centric AI (Zha et al., 2023) covers such task.

Memory and replay for LLMs continual learning. Before LLMs get popular in machine learning, continual learning studies in deep learning faced the challenge of data privacy. The situation gets different in LLM studies and applications. For example, one can separate pre-trained LLMs from user data with RAG (Lewis et al., 2020). From this perspective, it is interesting to see how post-training and finetuning leverage memory, RAG, and replay for continual learning.

Relation to LLM.

These works may not necessary aim at continual learning and turns out helping improve the performance. It is interesting to see that they could be interprete from continual learning perspectives. Well, not in this blog, perhaps in another block in this continual learning series.

- Mixture of Experts (MoEs (Shazeer et al., 2017)), Gating mechanisms (like in Qwen (Qiu et al., 2025)): this can be a static architecture-based method.

- RL-based post-training: Uniquely different from the existed methods, this enlights a new category of methods.

- EMA (like in DINO): this can be a regualarization-based method.

- Synthetic data as training data (in TabPFN (Hollmann et al., 2023)): this can be a replay-based method.

Further reading:

- Papers explain why RL post-training;

- MoE;

- Gating mechanism in Qwen.

References

- Qiu, Z., et al. (2025). Gated Attention for Large Language Models: Non-linearity, Sparsity, and Attention-Sink-Free. NeurIPS.

- Hollmann, N., et al. (2023). TabPFN: A transformer that solves small tabular classification problems in a second. ICLR.

- Mundt, M., et al. (2023). A Wholistic View of Continual Learning with Deep Neural Networks: Forgotten Lessons and the Bridge to Active and Open World Learning. Neural Networks.

- Zha, D., et al. (2023). Data-centric Artificial Intelligence: A Survey. arXiv.

- Caron, M., et al. (2021). Emerging Properties in Self-Supervised Vision Transformers. ICCV.

- Radford, A., et al. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. ICML.

- Lewis, P., et al. (2020). Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. NeurIPS.

- Finn, C., et al. (2017). Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning for Fast Adaptation of Deep Networks. ICML.

- Shazeer, N., et al. (2017). Outrageously Large Neural Networks: The Sparsely-Gated Mixture-of-Experts Layer. ICLR.

- Mnih, V., et al. (2013). Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv.